In October 1966, Gary Duncan, a 19-year-old African American, was driving along a Louisiana highway when he observed his younger cousins, who were African American, in the company of four white youths. Given the racial tensions following the recent desegregation of schools, Duncan was concerned for his cousins' safety. He stopped, encouraged his cousins to enter his car, and, according to some accounts, may have touched one of the white youths on the elbow. The white youths alleged that Duncan slapped one of them, leading to his arrest and subsequent charge of simple battery.

Under Louisiana law at the time, simple battery was classified as a misdemeanor, carrying a maximum penalty of two years' imprisonment and a $300 fine. Despite the potential severity of the punishment, Louisiana's constitution permitted jury trials only in cases where capital punishment or imprisonment at hard labor could be imposed. Consequently, Duncan's request for a jury trial was denied. He was tried before a judge, found guilty, and sentenced to 60 days in prison and a $150 fine.

Legal Issue

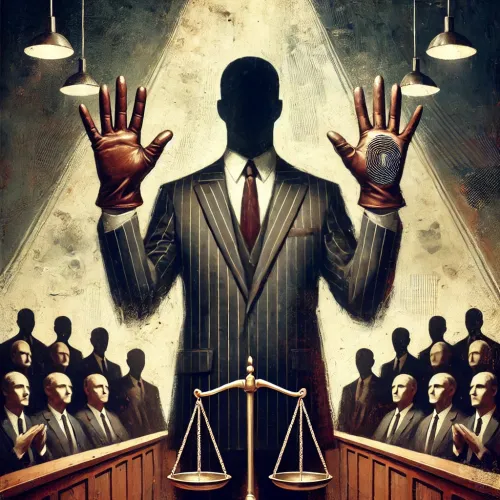

The central question before the U.S. Supreme Court was whether the Sixth Amendment's guarantee of a right to a jury trial in criminal cases is fundamental to the American scheme of justice and, therefore, applicable to the states through the Fourteenth Amendment's Due Process Clause. Specifically, the Court needed to determine whether denying Duncan a jury trial for a crime punishable by up to two years' imprisonment violated his constitutional rights.

Supreme Court Decision

On May 20, 1968, the Supreme Court, in a 7-2 decision, ruled in favor of Duncan. Justice Byron White, writing for the majority, held that the right to a jury trial is fundamental to the American justice system and is therefore incorporated against the states through the Fourteenth Amendment. The Court reasoned that juries serve as a vital safeguard against potential governmental oppression, ensuring that defendants are judged by a representative cross-section of the community.

The Court distinguished between "serious" and "petty" offenses, noting that the Sixth Amendment guarantees the right to a jury trial for serious offenses. While the Constitution does not explicitly define these terms, the Court referenced historical and contemporary standards, concluding that crimes punishable by more than six months' imprisonment are considered serious. Since Duncan's charge carried a potential two-year sentence, it qualified as a serious offense, entitling him to a jury trial.

Concurring and Dissenting Opinions

Justice Hugo Black, in his concurrence, advocated for the total incorporation of the Bill of Rights against the states, asserting that all its protections are fundamental and should apply uniformly. Justice Potter Stewart, dissenting, contended that the majority's decision imposed federal standards on states without sufficient justification, potentially undermining state autonomy in administering justice.

Implications for Jury Nullification

While Duncan v. Louisiana primarily addressed the right to a jury trial, it has implications for the concept of jury nullification—the ability of jurors to acquit defendants despite evidence of guilt if they believe the law is unjust or improperly applied. By affirming the fundamental role of juries in the criminal justice system, the decision implicitly acknowledges the jury's power to act as a check on governmental authority. This reinforces the idea that juries can serve as the conscience of the community, potentially exercising nullification in cases where strict application of the law would result in injustice.

Duncan v. Louisiana stands as a landmark decision in American constitutional law, reinforcing the right to a jury trial in serious criminal cases and ensuring that this protection extends to defendants in state courts. The ruling underscores the importance of juries as a fundamental component of the justice system, serving both as fact-finders and as a safeguard against potential governmental overreach. By incorporating the Sixth Amendment's jury trial guarantee through the Fourteenth Amendment, the Supreme Court affirmed the essential role of juries in upholding individual liberties and maintaining public confidence in the legal process.