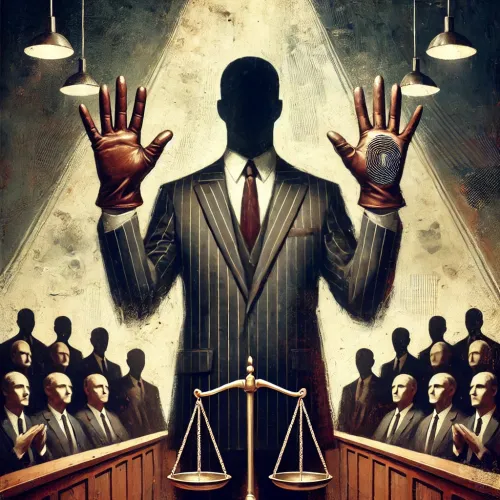

In the early 1990s, Grady Thomas and several co-defendants were indicted on federal narcotics charges, including conspiracy to possess and distribute cocaine and crack cocaine. The first trial ended in a mistrial due to a hung jury. A second trial commenced in November 1994 in the United States District Court for the Northern District of New York. During jury selection, the prosecution attempted to use a peremptory challenge to exclude Juror No. 5, the only remaining Black juror. The defense objected, citing Batson v. Kentucky, which prohibits racial discrimination in jury selection. The court found the prosecution's reasoning non-discriminatory but denied the challenge, allowing Juror No. 5 to remain.

Juror No. 5's Conduct

Throughout the six-week trial, several jurors expressed concerns about Juror No. 5's behavior, describing it as disruptive and indicating a potential bias. Complaints included making distracting noises and displaying agreement with defense arguments. The trial judge conducted individual interviews with the jurors to assess these concerns. Juror No. 5 maintained that his opinions were based on the evidence presented. Despite initial decisions to retain him, continued complaints led the judge to dismiss Juror No. 5, citing his unwillingness to deliberate based on the law and evidence.

Legal Issue

The central issue on appeal was whether the dismissal of Juror No. 5 was appropriate, particularly concerning the possibility that he was engaging in jury nullification—deliberately disregarding the law due to personal beliefs. The defense argued that the dismissal violated the defendant's right to a fair trial by an impartial jury.

Second Circuit Court of Appeals Decision

On May 20, 1997, the Second Circuit Court of Appeals delivered its opinion, affirming the district court's decision. The court held that a juror could be dismissed if there is clear evidence that the juror intends to nullify the law rather than apply it as instructed. The court emphasized that while jurors have the power to nullify, they do not have the right to do so, and deliberate disregard for the law constitutes grounds for dismissal.

Key Points from the Decision

- Distinction Between Power and Right: The court distinguished between the jury's power to nullify and the absence of a legal right to do so. While jurors can technically return a verdict contrary to the law, they are obligated to follow the court's legal instructions.

- Grounds for Dismissal: A juror may be dismissed if there is unambiguous evidence that the juror is unwilling to apply the law as instructed. In this case, the court found sufficient evidence that Juror No. 5 intended to nullify the law, justifying his removal.

- Preservation of Jury Deliberation Secrecy: The court acknowledged the importance of maintaining the confidentiality of jury deliberations but held that this principle does not preclude the dismissal of a juror who is demonstrably unwilling to adhere to legal instructions.

Implications

The United States v. Thomas decision has significant implications for the practice of jury nullification and the administration of justice:

- Limitation on Jury Nullification: The ruling reinforces the judiciary's position that while jurors have the power to nullify, they are not entitled to do so, and deliberate nullification can lead to dismissal.

- Judicial Oversight: The decision underscores the court's authority to ensure that jurors adhere to legal instructions, maintaining the integrity of the legal process.

- Jury Deliberation Confidentiality: The case highlights the tension between preserving the secrecy of jury deliberations and the need to address potential juror misconduct, suggesting that confidentiality does not shield a juror from dismissal if there is clear evidence of intent to disregard the law.

United States v. Thomas serves as a pivotal case in understanding the boundaries of jury nullification within the American legal system. By upholding the dismissal of a juror intent on nullifying the law, the Second Circuit Court of Appeals reinforced the principle that jurors are obligated to apply the law as instructed, ensuring the rule of law prevails in judicial proceedings.