In the mid-19th century, the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 became one of the most contentious laws in American history, pitting federal authority against the conscience of free-state communities. As part of the Compromise of 1850, the Act required citizens and officials in free states to assist in the capture and return of escaped enslaved individuals. It imposed harsh penalties on anyone aiding fugitives or obstructing their capture, further entrenching the institution of slavery in American law.

Despite its legal authority, the Fugitive Slave Act faced widespread resistance, particularly in the North. Beyond organized protests and civil disobedience, jury nullification emerged as a powerful tool for communities to reject this law. Northern juries, composed of citizens morally opposed to slavery, frequently acquitted individuals charged under the Act, even when evidence clearly showed violations.

One of the most famous cases illustrating this resistance occurred in Syracuse, New York, in 1851. William “Jerry” Henry, an escaped enslaved man, was arrested under the Fugitive Slave Act. His detention sparked outrage among abolitionists, who staged a dramatic rescue. Hundreds of citizens stormed the jail, freeing Henry and helping him escape to Canada. Several individuals involved in the rescue were later prosecuted, but local juries refused to convict them, effectively nullifying the law.

Another significant case unfolded in Boston that same year, involving Shadrach Minkins, an escaped enslaved man working as a waiter. Federal marshals arrested Minkins under the Fugitive Slave Act, but local abolitionists quickly mobilized. In a coordinated effort, they freed Minkins from custody and spirited him away via the Underground Railroad to Canada. Subsequent trials of those who aided in Minkins’ escape resulted in similar outcomes: Northern juries refused to convict.

These acts of defiance were not isolated incidents but part of a broader pattern of resistance. In state after state, jurors demonstrated their unwillingness to enforce a law they deemed morally abhorrent. They saw themselves not merely as arbiters of legality but as defenders of justice. Their refusal to convict under the Fugitive Slave Act undermined its effectiveness, emboldening abolitionist efforts and sending a clear message about the growing moral divide in America.

Jury nullification in these cases highlighted a profound tension between federal authority and local moral values. The Fugitive Slave Act was designed to enforce national unity on the issue of slavery, but it achieved the opposite. Instead, it deepened sectional animosities and galvanized the abolitionist movement, making the institution of slavery increasingly untenable.

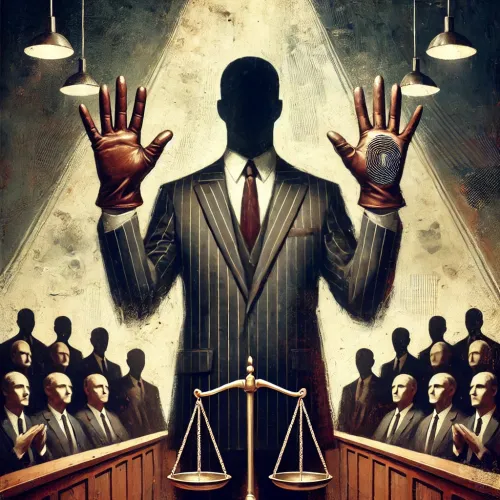

Critics of jury nullification have long argued that it undermines the rule of law by allowing jurors to substitute personal beliefs for legal standards. However, in the context of the Fugitive Slave Act, nullification became a form of moral resistance. It enabled ordinary citizens to challenge the legitimacy of an unjust law and assert their commitment to higher ethical principles.

The Fugitive Slave Act cases exemplify the complex interplay between law and morality. While the Act represented the federal government’s attempt to preserve the institution of slavery, the actions of nullifying juries reflected the growing belief that slavery was incompatible with the principles of liberty and justice. This tension would ultimately culminate in the Civil War, where the question of slavery was decided not in courtrooms but on battlefields.

The legacy of jury nullification during this period is profound. It demonstrates the power of local communities to resist and influence national policies. It also underscores the importance of juror independence in the American legal system. By prioritizing justice over legality, nullifying jurors in the 1850s contributed to the larger movement that eventually led to the abolition of slavery.

Today, the Fugitive Slave Act and the jury nullifications that opposed it serve as powerful reminders of the enduring struggle for justice in the face of systemic oppression. They highlight the potential for ordinary citizens to enact change, even when faced with seemingly insurmountable legal and political structures. In defying an unjust law, these jurors upheld the ideals of freedom and human dignity, leaving a legacy that continues to inspire those who fight for justice in modern times.