The story of John Peter Zenger's 1735 trial exemplifies the enduring tension between authoritarian governance and the rights of individuals—a conflict that continues to define democracy. This case, often heralded as a cornerstone of American liberty, demonstrated the transformative power of jury nullification in resisting unjust laws.

Zenger, a German immigrant and printer, operated the New York Weekly Journal, a publication that openly criticized Governor William Cosby. Among the allegations were claims of corruption and abuse of power. Incensed by the articles, Cosby had Zenger arrested on charges of seditious libel—a crime punishable by imprisonment. At the time, English law dictated that truth was not a defense; the mere act of publishing criticisms of the government constituted libel.

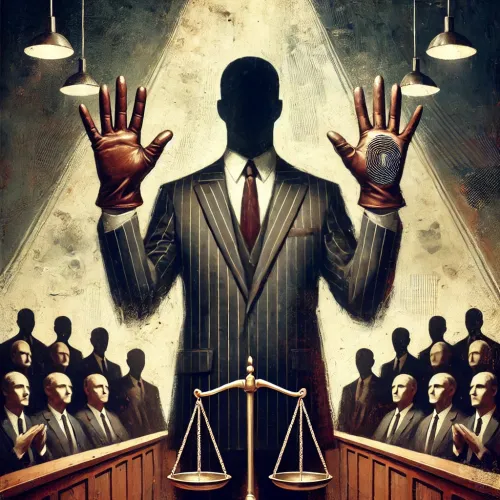

As the trial began, the case against Zenger seemed ironclad. The judge, aligned with Cosby, instructed the jury to consider only whether Zenger had printed the articles in question—a fact Zenger did not contest. By this narrow interpretation, the law demanded a guilty verdict.

However, Zenger's defense attorney, Andrew Hamilton, employed an audacious strategy that turned the trial into a referendum on the principles of free speech and press. Hamilton implored the jury to look beyond the letter of the law and consider its moral implications. He argued that punishing Zenger for exposing governmental wrongdoing was a direct assault on liberty.

“Are we to allow tyrants to silence truth?” Hamilton questioned, appealing to the jury’s sense of justice. He emphasized that the jury had a duty not only to weigh the facts but also to safeguard the principles of a free society. His argument hinged on the notion that jurors were not mere enforcers of the law but guardians of justice.

The judge attempted to stifle this line of reasoning, directing the jury to disregard Hamilton's arguments. Nevertheless, the jurors defied the judge’s instructions, acquitting Zenger in what became one of the earliest examples of jury nullification in colonial America.

The verdict sent shockwaves through the colonies. For the first time, ordinary citizens had used their role in the judicial process to challenge an unjust law and uphold broader principles of justice. The trial emboldened the colonial press, encouraging more outspoken critiques of government authority. Over time, it laid the groundwork for the First Amendment, which enshrines freedoms of speech and press in the U.S. Constitution.

Zenger’s case also highlighted the immense power vested in juries. Jury nullification, while controversial, has remained an essential check against oppressive legislation. By acquitting Zenger, the jurors rejected a rigid application of the law in favor of protecting fundamental rights. Their decision underscored the importance of conscience in the judicial process, reminding future generations that justice sometimes requires defiance of the status quo.

Critics of jury nullification argue that it undermines the rule of law by allowing jurors to substitute personal biases for legal standards. However, its proponents maintain that it serves as a critical safety valve in a democracy, particularly when laws fail to reflect the values of the community. The Zenger trial exemplifies the positive potential of nullification when guided by principles of justice and equity.

In contemporary contexts, jury nullification continues to spark debate. It has been employed in cases ranging from the Fugitive Slave Act to drug-related prosecutions, reflecting evolving societal values. Yet, the Zenger trial remains a unique and enduring symbol of its power to protect individual freedoms.

Nearly three centuries later, the trial of John Peter Zenger is remembered not only as a victory for one man but as a triumph for the ideals of free expression and democratic accountability. It serves as a reminder that the courage of ordinary citizens, armed with principles and a sense of justice, can change the course of history. Through their defiance, Zenger’s jurors taught future generations that laws serve society best when they reflect its highest ideals—and that justice often begins in the hearts of the people.