On May 17, 1968, Mary Moylan, along with seven other individuals, entered the office of the local draft board in Catonsville, Maryland. They removed approximately 378 draft files and proceeded to burn them in an adjacent parking lot using homemade napalm. This act was a deliberate protest against the Vietnam War, intended to disrupt the Selective Service System and draw attention to their anti-war stance. The participants openly admitted to their actions, framing them as morally justified civil disobedience.

Legal Proceedings

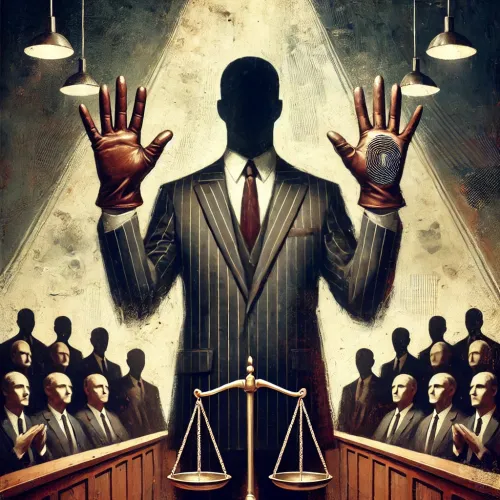

The protesters were indicted and tried in the United States District Court for the District of Maryland, facing charges including the mutilation of government records, destruction of government property, and interference with the administration of the Selective Service System. During the trial, the defendants did not dispute the facts but sought to introduce a defense based on the moral imperative of their actions, arguing that their intent was to prevent greater harm by protesting the war. They requested that the jury be instructed on their power to acquit despite the evidence—a concept known as jury nullification.

District Court Ruling

The trial judge refused to instruct the jury on the concept of jury nullification and prohibited defense counsel from arguing this point to the jurors. The defendants were subsequently convicted on all counts. They appealed the conviction to the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals, asserting that the trial court erred in its instructions to the jury, particularly concerning the definition of criminal intent and the refusal to inform the jury of their nullification power.

Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals Decision

On October 15, 1969, the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals delivered its unanimous decision, authored by Judge Simon Sobeloff, affirming the convictions. The court addressed two primary contentions raised by the appellants:

- Definition of "Willfully": The appellants argued for a broader interpretation of "willfully," suggesting that their actions, motivated by a desire to protest an immoral war, lacked the bad purpose necessary for criminal liability. The court rejected this argument, stating that the defendants knowingly and purposely committed the acts prohibited by statute, fulfilling the requisite intent for conviction.

- Jury Nullification Instruction: The appellants contended that the trial judge should have informed the jury of their power to acquit despite the law and evidence. While the court acknowledged the jury's de facto power to acquit against the evidence and law, it held that neither the court nor counsel are required to inform the jury of this power. The court emphasized that promoting such an instruction could lead to anarchy and undermine the rule of law.

Significance of the Decision

The United States v. Moylan decision is significant for several reasons:

- Recognition of Jury Power: The court recognized the jury's inherent power to acquit against the evidence and law, acknowledging the historical role of juries as a check on potential governmental overreach.

- Limitation on Jury Instructions: The ruling established that courts are not obligated to inform juries of their nullification power, nor should attorneys encourage jurors to disregard the law. This limitation aims to preserve the integrity and predictability of the legal system.

- Impact on Civil Disobedience Cases: The case set a precedent for how courts handle defenses based on moral or political motivations, particularly in instances of civil disobedience, by focusing on the legality of actions rather than the intent behind them.

Implications for Jury Nullification

The Moylan decision underscores the delicate balance between acknowledging the jury's power to nullify and maintaining judicial authority. By refusing to mandate jury instructions on nullification, the court sought to prevent potential misuse of this power, which could lead to inconsistent verdicts and undermine the rule of law. At the same time, the decision preserved the jury's role as a safeguard against unjust laws, allowing for the possibility of nullification without formal endorsement.

United States v. Moylan remains a pivotal case in the discourse on jury nullification within the American legal system. It highlights the judiciary's recognition of the jury's power to acquit against the law and evidence while reinforcing the principle that such power should not be actively promoted or instructed by the courts. This case continues to influence legal perspectives on the role of juries, civil disobedience, and the boundaries of lawful protest.