The Civil Rights Movement of the mid-20th century marked a transformative period in American history, as activists sought to dismantle the entrenched system of racial segregation and discrimination. Yet, during this struggle for equality, the courtroom often became a battleground where justice was denied. All-white juries, particularly in the Jim Crow South, frequently acquitted white defendants accused of heinous crimes against Black victims, perpetuating the racial inequality activists sought to eradicate.

One of the most infamous examples of this occurred in 1955, with the murder of Emmett Till, a 14-year-old Black boy visiting family in Mississippi. Till was accused of whistling at a white woman, Carolyn Bryant, an act considered a grave transgression in the racially segregated South. Shortly after, he was abducted, brutally beaten, and murdered by Roy Bryant and J.W. Milam, who then dumped his body in the Tallahatchie River. The evidence against Bryant and Milam was overwhelming, including eyewitness testimony and their subsequent public confession. Yet, the all-white jury deliberated for only an hour before delivering a verdict of "Not Guilty," citing a lack of definitive proof.

Similarly, during the Freedom Summer of 1964, three civil rights workers—James Chaney, a Black man, and Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner, both white—were murdered in Mississippi while registering Black voters. The investigation revealed that the killings were orchestrated by members of the Ku Klux Klan with the complicity of local law enforcement. Despite the perpetrators being identified and federal charges being brought, convictions were scarce and penalties were minimal. The local juries displayed blatant racial bias, showing little interest in justice for the victims.

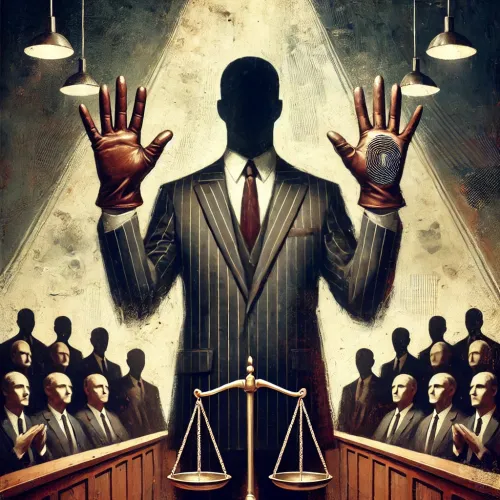

These acquittals, and countless others like them, were acts of de facto jury nullification. Unlike traditional nullification, where jurors resist enforcing laws they find unjust, these verdicts reflected a deliberate disregard for evidence to uphold white supremacy. Jurors in these cases prioritized racial solidarity over legal duty, shielding white defendants from accountability for their crimes against Black individuals.

The implications of these verdicts were profound and far-reaching. For Black communities, they confirmed the systemic racism of the judicial system and underscored the need for federal intervention to ensure justice. For civil rights activists, these cases became rallying cries that galvanized the movement. The stark injustice of Emmett Till’s murder, in particular, drew national and international attention, sparking outrage that fueled the fight for change.

However, the persistence of these unjust acquittals also exposed the limitations of jury nullification as a tool for justice. While nullification can serve as a powerful check on oppressive laws, as seen in cases like those resisting the Fugitive Slave Act, it can also be wielded as a weapon to perpetuate systemic inequities when jurors act on prejudices rather than principles. The Civil Rights Movement illuminated the double-edged nature of this judicial mechanism.

Over time, the activism sparked by these injustices led to significant legal and societal changes. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 dismantled many institutional barriers to equality. Additionally, the inclusion of more diverse juries became a priority, with the Supreme Court ruling in cases like Batson v. Kentucky (1986) to prohibit racial discrimination in jury selection.

Despite these advancements, the legacy of all-white juries during the Civil Rights era remains a cautionary tale. It serves as a reminder of the power jurors hold and the consequences of allowing personal biases to overshadow the pursuit of justice. The actions of these juries perpetuated a cycle of violence and oppression, delaying progress and deepening societal divisions.

Today, discussions about jury nullification often invoke its potential for both good and harm. While it can challenge unjust laws, as seen in cases involving the Fugitive Slave Act or Prohibition, it can also perpetuate injustice when wielded irresponsibly. The Civil Rights era cases underscore the importance of an impartial and representative jury system—one that reflects the diversity and values of the community it serves.

The story of all-white juries in the Jim Crow South is a stark reminder of the stakes involved in jury deliberations. Jurors are not mere fact-finders; they are moral agents whose decisions shape the course of justice. When guided by prejudice, their power can be a force for oppression. But when guided by conscience and fairness, it can challenge injustice and uphold the principles of equality and human dignity.

In reflecting on these cases, we are reminded of the critical role jurors play in the legal system. Their decisions not only determine individual outcomes but also reflect and shape societal values. As the Civil Rights Movement demonstrated, the pursuit of justice is not solely the responsibility of lawmakers and judges—it is a collective endeavor, requiring vigilance and moral courage at every level, including the jury box.